Insights and Commentaries

CCS remains a critical technology according to Princeton University’s Professor Emeritus Robert Socolow

16th February 2016

Topic(s): Carbon capture, Economics, use and storage (CCUS)

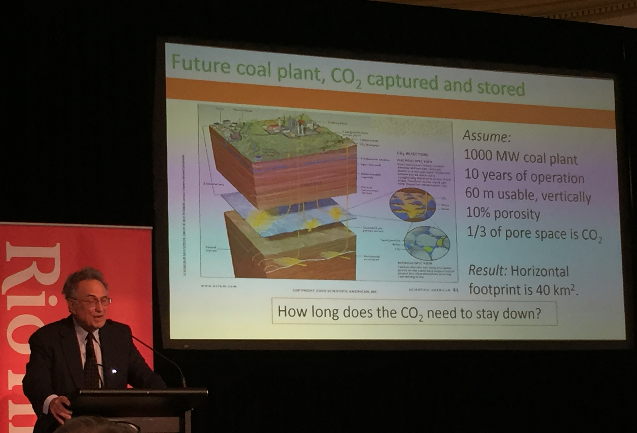

On 9 February 2016, Professor Robert Socolow of Princeton University gave a breakfast lecture in Brisbane about the future of fossil fuels within a context of climate change mitigation. Professor Socolow’s seminal work in 2004 demonstrated that reducing emissions could be achieved using commercially available technologies. His paper Stabilization Wedges: Solving the Climate Problem for the Next 50 Years with Current Technologies included carbon capture and storage (CCS) on power, coal synfuels and hydrogen production to stabilise atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide at 500ppm (commensurate with global climate ambitions at the time). Professor Socolow strongly reaffirmed this view again in his lecture, and concluded that there is a very real and urgent need to support CCS, especially for low-cost CO2 capture opportunities such as gas processing.

“Acting urgently on climate presents us all with a cognitive dissonance”

The dissonance to which Professor Socolow refers is his belief that fossil energy remains as vital to the world economy today as it has in the past while the immovable challenge of addressing climate change clearly “looms ominously”. He opened his lecture with the following question to the audience: Which quadrant are you? (see table below, from Robert Socolow's presentation).

| Are fossil fuels hard to displace? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Is climate change an urgent matter? | No | A nuclear or renewables world unmotivated by climate | Most people in the fuel industries and most of the public are here 5°C |

| Yes | Environmentalists, nuclear advocates are often here 2°C | Why we're in the room 3°C |

|

No-one in the 100 strong audience (many of whom represented major resource companies) suggested that urgent action was not needed on climate, leaving quadrants 1 and 2 completely unrepresented. Only a handful of attendees selected quadrant 3 that indicated urgent action was needed and that it was easy to displace fossil based energy (Socolow described these respondents as generally being very pro-renewable energy). Some 90% of the audience selected quadrant 4 indicating that climate action is urgent and fossil energy is hard to displace.

In quantifying how these respective ‘views’ might translate to average global temperature rises given the expected scale of climate mitigation, Professor Socolow identified that quadrant 3 could probably meet a 2°C goal while quadrant 4 is broadly equivalent to a 3°C rise and quadrant 2 could lead to a 5°C rise. If the views of this Brisbane-based audience serve as a proxy for global action, and Professor Socolow’s numbers are right, then it seems the world is tracking on a 3°C trajectory – far in excess of the COP21 climate goal of between 1.5°C and 2°C. In regards to quadrant 4, Professor Socolow indicated that such an outcome would inevitably rely increasingly on the contribution of negative emissions as generated by afforestation and CCS coupled with bio-energy (BECCS); a conclusion very much supported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 5th Assessment Report.

Fossil energy will continue to play a vital energy role

Professor Socolow also spoke of the challenges he saw with some of the ‘unburnable fossil fuel’ arguments that aim to avoid emissions from remaining fossil resources. He observed that the available known fossil resources (still in the ground) are equivalent to 8,000 billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) from oil, 3,000 GtCO2 from gas, and 20,000 GtCO2 from coal. He further observed that even if one wanted the resources to remain underground, it would be virtually impossible for anyone in the world to decide which resources should remain there let alone give effect to such decisions.

Professor Socolow also drew on what he sees as shortcomings of the ‘fossil divestment’ arguments (as largely represented by quadrant 3 type views in the photo above). Such arguments tend to assume that emissions from known fossil reserves can be avoided by stranding the current fleet of fossil assets in the short term. In his view the current fleet of fossil assets will not be economically stranded as long as they continue to add value to the fossil resource base. Divestment of next generation assets may be possible, targeting new investment to expand current fossil fuel reserves and/or build new long-lived infrastructure, but this would be too late to preserve the 2°C global carbon budget.

Considering the potential CO2 emissions in available fossil resources coupled with the difficulty in identifying which resource should remain ‘unburned’, CCS must be allowed to play its critical role as being realistically the only technology that can deal effectively with this issue.

Inducing change through carbon pricing

With reference to carbon pricing, Professor Socolow suggested that unless the carbon price can trend over time to a US$100 per tonne threshold with compliance placed as far upstream in the resources chain as possible then it will be hard to get industry to induce new investment in the portfolio of technologies needed. This is not only for CCS but also renewables, energy efficiency and nuclear power.

Still cause for optimism

In his final observations for the night Professor Socolow expressed optimism in the ability of policy makers and industry alike to address climate change in a timely manner by noting that most of the 2065 global infrastructure is not yet built (allowing for it to be engineered). He strongly promoted the role of CCS within the context of helping deliver on the climate goals recently adopted at COP21 (noting the role of CCS for both mitigation its ability to generate negative emissions when coupled with bio-energy).