Insights and Commentaries

Lessons learned from CCS development in the North of the Netherlands

15th February 2015

Topic(s): Public engagement

By Barend van Engelenburg (DCMR Milieudienst Rijnmond) and Hanneke Puts (TNO)

The planning processes for developing and implementing new, innovative technologies like carbon capture and storage (CCS) take place in complex political, societal, economic and technical environments. Such planning processes can easily become intangible and complex due to their multi-level, multi-stakeholder and multi-issue characteristics. Gaining insight into the complexity and dynamics of these processes can help future developers, decision makers and other key stakeholders involved in developing new CCS (or other innovative energy) projects.

In this Insight, Barend van Englenburg from CMR Centre for Environmental Expertise and Hanneke Puts, TNO, present an overview of the Dutch planning process for CCS projects in the North of the Netherlands. They take the reader on a review of the the ‘Learning History’ approach, providing high level findings from a confidential research project into CCS in the the North of the Netherlands. Although the detailed results of this research project are confidential, by sharing the overall approach that was taken, the authors seek to pass on a variety of interesting lessons learned and recommendations for future innovative energy projects.

Authors: Barend van Engelenburg, DCMR Centre for Environmental Expertise, The Netherlands and Hanneke Puts, TNO – Strategy & Policy for Environmental Planning, The Netherlands. The Learning History study was part of the Dutch CCS Research Program CATO2 and was performed by the authors. Tara Geerdink and Mario Willems (both TNO) and Emma ter Mors (Leiden University) supported us in this study.

Situation

The planning process for CCS in the North of the Netherlands formally started in 2007 due to a political decision in the province of Groningen. The Government planned to connect the preparation of the two new coal fired power stations to CCS technology. The planning process more or less ended on the 14th of February 2011, after a decision by the Dutch Government to indefinitely postpone onshore carbon dioxide (CO2) storage in the Netherlands, mainly due to a lack of public support.

Goal: gaining insight into complexity

The focus of our research was to unravel and understand the planning process, including the roles, interests and interactions of the different stakeholders given the political and societal dynamics at that time. The aim of the project was to provide lessons to support future developers, decision makers and other key stakeholders for CCS projects, in order to improve the ability of developers to cope with the complex context in which the new technology has to be implemented. Moreover, these results are thought to be applicable for other innovative energy projects that have to be implemented in politically and socially complex environments, like wind energy or biomass projects.

Confidentiality

The CATO2 Executive Board was keen on learning lessons from the CCS case in the North of the Netherlands, by composing a reconstruction of the planning process. However, some of the directly involved stakeholders were somewhat reluctant to participate in the proposed research project. Therefore, the CATO2 Executive Board agreed to support a confidential case study. According to the condition of confidentiality, the contributions of both the interviewees and the external experts have been processed anonymously.

Although the full document cannot be shared with anyone outside the group of stakeholders who have been participating in the Learning History study, we can share their lessons learned, along with the recommendations.The confidentiality of their input and the final results was highly important for the directly involved stakeholders: due to this condition they became willing to share their experiences and personal reflections in a very open way and even gave access to all documents which they found relevant for the reconstruction of the planning process.

‘Learning History’ method

As a systematic approach for the evaluation of (organisational) processes, the researchers at TNO and DCMR applied the so-called ‘Learning History’ (LH) approach. The rationale for this choice was the fact that the LH approach is not only descriptive and analysing, but also activates individuals and organisations to learn. The LH method is an organisational reflection process, in which researchers and stakeholders closely work together. In the late 1990s, George Roth and Art Kleiner at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston developed the method, as a response to the limitations of more traditional assessments of organisational processes.

The strength of the LH approach is that it tells the story about the planning process of the CCS case in the North-Netherlands, from the perspective of the most relevant stakeholders involved. The LH is built on three levels:

- Factual events: What happened during the planning process?

- Personal experiences of directly involved stakeholders.

- Reflections on the factual events and personal experiences by external, non-involved experts.

The factual events and personal experiences of the stakeholders involved were gathered from a quick scan document analysis, 16 interviews with 20 stakeholders and two workshops. The interviewees originated from:

- industry and local,

- regional and national governments

- politicians

- policy advisors

- employees from private companies, and

- communication experts.

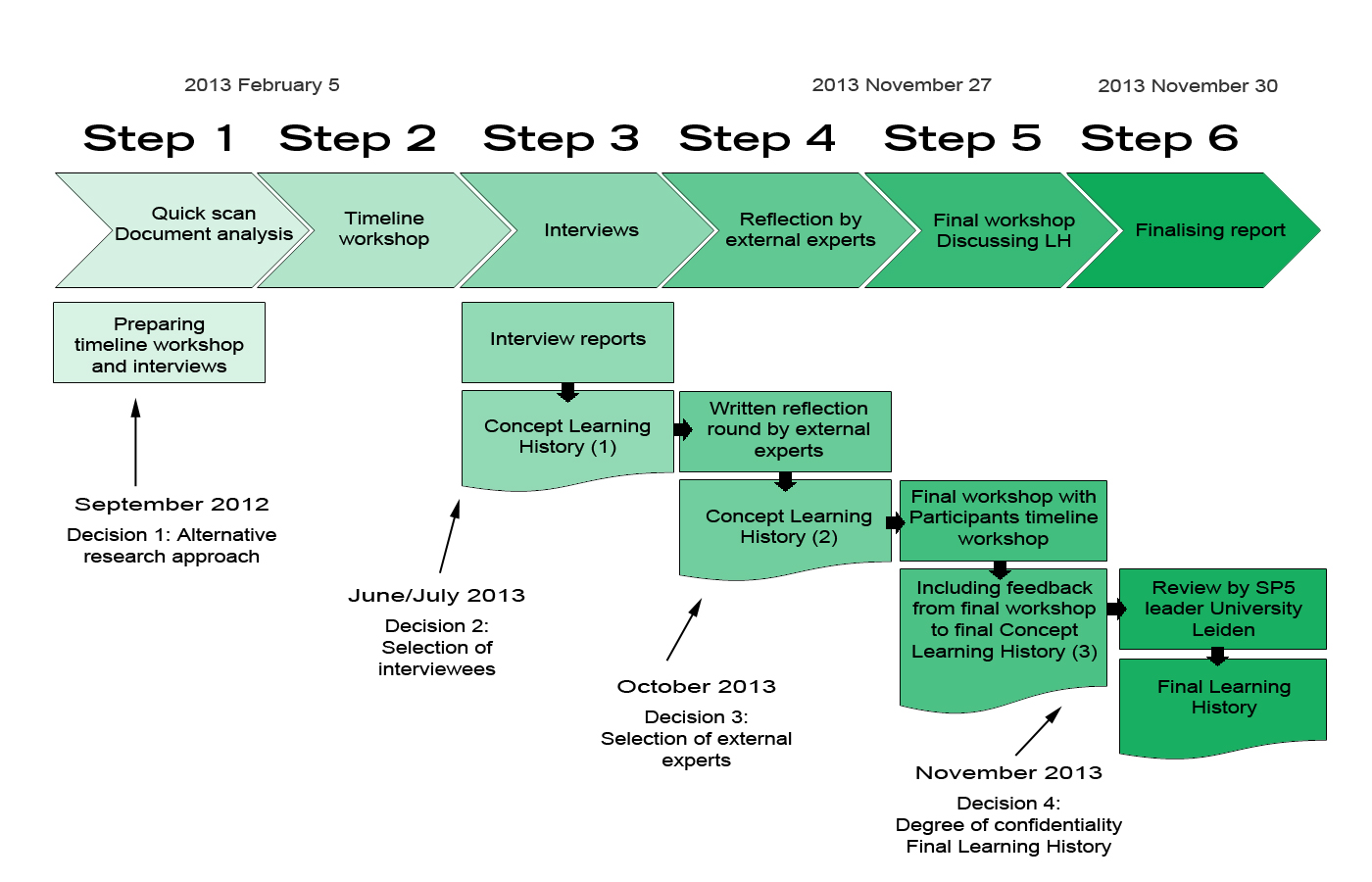

The LH was written based on these steps. Before the last workshop, five independent experts from science, government (2x), risk communication and industry were invited to reflect on the draft LH. These external experts were selected due to their knowledge of, and experiences with, similar planning processes in a complex and dynamic environments. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: research steps towards the final Learning History.

Conclusions

The final LH contains a detailed and actual description of the course of events regarding the planning process of the CCS initiatives in the North of the Netherlands, combined with personal experiences of involved persons and reflections of non-involved experts based on our confidentiality criteria outlined above.

Lessons Learned

Our participants defined the following lessons learnt:

- “Energy is politics” – Both public and private stakeholders became aware that the development and implementation of an innovative project or technology involves far more than the technology itself. Respondents found that due to the complexity of the planning process involving more than a single techno-economical challenge, they soon become part of a “political” playing field.

- Time and Timing – The stakeholders ascertained that the development and implementation of a new, innovative and unknown technology requires a proper introduction into civil society. This was felt to be especially important when there was not (yet) a commonly accepted social need for the new technology, like in the case of CCS. In addition, communication towards (and with) the general public about a new and unknown development takes time. However, in this case, there was a shortage of time to develop a proper communication approach due to the strict deadline for the planning process. This deadline was set by the demands of the European subsidy program NER300, which aimed to be one of the main financing sources of the planned CCS projects in the Netherlands. Lastly, it does not help the planning process when a dialogue can only have one possible outcome such as the realisation of one or more concrete CCS projects in the North of the Netherlands. Rather, for a dialogue to be successful, it should be open to alternative perspectives and solutions.

- Sharing and handling of different stakeholder interests – The stakeholders involved felt that there was too little attention paid to the different perspectives and interest of stakeholders involved in the planning process. They believe that it would have greatly improved the process if these different stakeholder perspectives had been better understood. Understanding the differences in stakeholder concerns would help developers to create a more targeted communication strategy that provides the general information required, but is flexible enough to tackle any new, specific issues that emerge.

- Providing information and technical knowledge – All the stakeholders involved in this process highlighted the importance of providing facts and gaining knowledge about the new technology in order to be able to form an opinion and/or take a decision. All stakeholders felt that it was critical to have a clear and complete technical storyline - citizens are very sensitive to any hints of uncertainty or ‘shaky’ storylines and this greatly undermines the trust they are willing to bestow on the person communicating with them. It was also very clear that it is a difficult skill to strike the correct balance between the input of facts and knowledge on the one side, and more emotive communication that helps tackle concerns on the other. It does not make sense to produce 'watered down' messages or what might be perceived as fact heavy, one-way communication when the stakeholders themselves are responding emotionally and with concern. During emotionally heightened periods of communication, using facts to try and “get rid of” the emotion has been shown to backfire on proponents. Striking the right balance between facts and emotion is very important, along with the ability to listen and reflect.

- Cooperation between different levels of Government – In the case of the North Netherlands, both the national, regional and local governments were involved. The directly involved stakeholders learned that achieving strong cooperation between these decision-making levels is crucial for a successful planning process. They found that the challenge is to get all parties willing to explore areas of common interests and to jointly define the next steps in the planning process. It is also recommended that developers make better use of the knowledge and experiences at each decision making level in order to be successful. This means that any national, regional and local governments involved need to handle each other with respect and equality.

- Transparent decision making process – In order to support trust and cooperation between stakeholders, transparency about the steps in the decision making process, as well as the role of information, knowledge and research on which decisions are being made become a crucial element. In this case, several stakeholders felt they missed this transparent way of working and communicating. From their experience, it is important for the planning process to understand how decisions are being made and why people choose a certain position in the discussion or negotiation.

- Steady leadership – Due to the political and societal dynamics in the planning process for the development of CCS projects in the North of the Netherlands, stakeholders perceived that decisions and strategies were volatile and unpredictable. Having strong, consistent, senior ambassadors for the technology/projects/policy would help instil more confidence in the process and the technology.

Recommendations for future (socially complex) energy projects

We identified the following recommendations based on the lessons learnt and perspectives of the stakeholders involved. This included input from external, independent experts:

- There is a need for clear and steady leadership: one visible captain preferably with 'natural authority'.

- Focus on organising an inclusive consultation and planning process, rather than trying to push the process towards a pre-determined result.

- Furthermore, the process approach should be clear, but also flexible and cover the whole planning process, including explicitly defined responsibilities.

- A dialogue only works if adjustments and alternative outcomes are possible. Otherwise, it becomes a one way communication strategy struggling to convince others of a particular point of view rather than a two way dialogue or negotiation.

- The conditions or ‘ground rules’ for the decision making process should be clear for all stakeholders involved. The following questions can help illustrate ground rules:

- who will make which decisions based on what evidence?

- what is the role of the stakeholders involved?

- what is the role of research?

- what issues can/can’t be discussed within the dialogue?

- what is the time frame for the decision making process?

The above overview of the most relevant lessons learned and recommendations for new, innovative (energy) projects is the result of a Learning History approach, which attempts to tell the story through the eyes of the stakeholders involved. Although it is tempting to add our own observations and reflections to the list of recommendations, we have chosen to restrict ourselves from sharing personal observations and opinions in this first Insight. In a second Insight on this case study the authors will give their personal reflections on the described CCS case study and on what they have learned in a broader perspective.