Insights and Commentaries

CCS Commercial and Regulatory Frameworks Enabling CCS Progress in Norway and Europe

Lessons learned from CCS front-runners during recent GCCSI webinar

18th December 2023

Key Insights:

- A comprehensive approach to CCS is required at a national level for the technology to play its role in climate mitigation. As a leader in CCS, Norway has been building up support, regulatory frameworks, expertise and experience with this technology for more than two decades.

- For CCS to be cost-competitive, it is crucial to build the business case in partnership with project developers, customers and authorities. The first CCS project at the Sleipner gas field was the result of a business case created by the Norwegian CO2 tax on offshore oil and gas operations.

- To implement complex full-scale CCS chains, both national subsidies and public-private forms of collaboration play a crucial role. More funding at the EU and national level are also needed to help CCS projects get off the ground.

- A fit-for-purpose regulatory framework is needed that can be applied to the business case for CCS hubs and clusters, as well as to multimodal and cross-border transport patterns.

- While there is an increasing number of CCS projects in Europe, there is currently no developed commercial market for CO2 transport and storage across the region. This mismatch between CO2 planned capture and available storage capacity makes taking steps towards the development of new storage reservoirs essential.

- The permitting process needs to accelerate in order to build CCS projects more rapidly. Additional human and technical capacity is required to speed up these processes.

- The short-term priority is to start transporting and storing CO2 as soon as possible. Establishing bilateral agreements can facilitate the transboundary movement of the CO2 and provide clarity on the state responsibility, reporting mechanisms and long-term liability.

- A risk-sharing mechanism for long-term CO2 liability is necessary. This could include an industry-wide insurance scheme and a national or regional fund to facilitate the financial security of long-term CO2 liability.

- The recognition and acceptance of CCS as a crucial climate mitigation solution is growing and the market is showing an increasing level of interest in CCS in Europe.

Introduction

In 1996, Norway launched the world’s first offshore CCS project developed for the purpose of CO2 storage. Since then, the country has played a leading role in the growth of the CCS market in Europe due to its capacity to provide CO2 storage for both domestic and cross-border CCS projects. Supportive policy frameworks are also driving new investment in the technology.

On 13 March 2023, the Global CCS Institute hosted a webinar assessing the state of CCS commercial and regulatory frameworks in Norway, and their impact on the development of CCS in the country.

During the webinar’s presentations and panel discussion, representatives from Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, Gassnova, Northern Lights, Altera Infrastructure and Equinor assessed the key factors and conditions enabling CCS deployment in the country. The panel members shared lessons learned from the implementation of important CCS projects, and views on the way forward to facilitate the expansion of the CCS market in Norway and Europe more broadly.

The Evolution of CCS in Norway

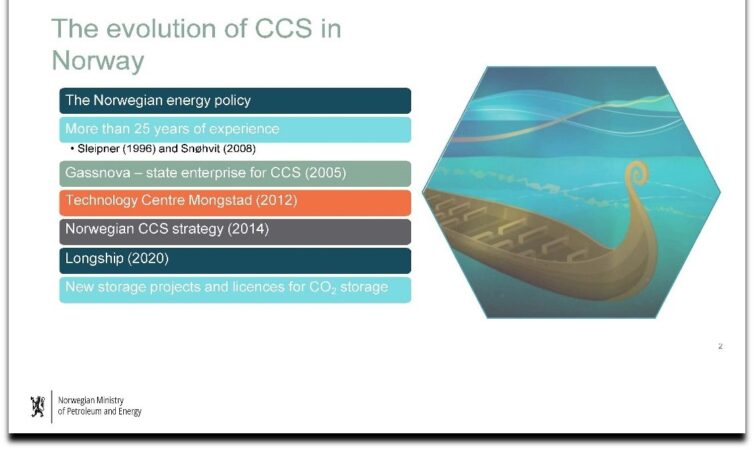

Norway has more than 25 years of experience with CCS, and the beginning of the country’s CCS journey dates back even earlier. Stig Svenningsen, Deputy Director General of Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, provided a comprehensive overview of the evolution of CCS in the country and recalled the leading role played by Norway in the framework of the World Commission on Environment and Development chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland, who later became the Norwegian Prime Minister.

Figure 1: The Evolution of CCS in Norway[1]

Established in 1983 by the United Nations General Assembly[2], the Brundtland Commission provided the best-known definition of sustainable development, and a conceptual framework that was later reflected in the Rio Declaration and the UNFCC Convention[3]. As a result of the work conducted by the Brundtland Commission and Norway’s objective to incentivise the reduction of CO2 emissions, the country in 1991 established a CO2 tax for offshore oil and gas activities, which led to the construction of the first CCS project at the Sleipner gas field.

During the planning phase of the Sleipner project located in the Norwegian part of the North Sea, it became clear that the natural gas contained about 9% CO2, exceeding gas market specifications of a maximum of 2.5% CO2. As a result, the CO2 content had to be reduced before the natural gas could be sold. Due to the Norwegian CO2 emissions tax, it was more economical to store the CO2, once captured than vent it, which would have cost the Sleipner West field around NOK 1 million/day in Norwegian CO2 taxes.

Setting the CO2 tax for offshore activities was just the beginning. In 2000, the Norwegian government made the decision to combine new gas-fired power plants with CCS. In 2005 the Norwegian state enterprise Gassnova was created to provide assistance with questions related to CCS. 2008 was also a crucial year for the development of CCS at national level, with the construction of the second CCS project, Snøhvit.

In 2012, the Norwegian Government led by Jens Stoltenberg set the obligation for all new power plants in the country to be built with CCS. During the same year, the world’s largest test centre for CO2 capture, the Technology Centre of Mongstad, came into operation to test the technology, and scale it up globally.

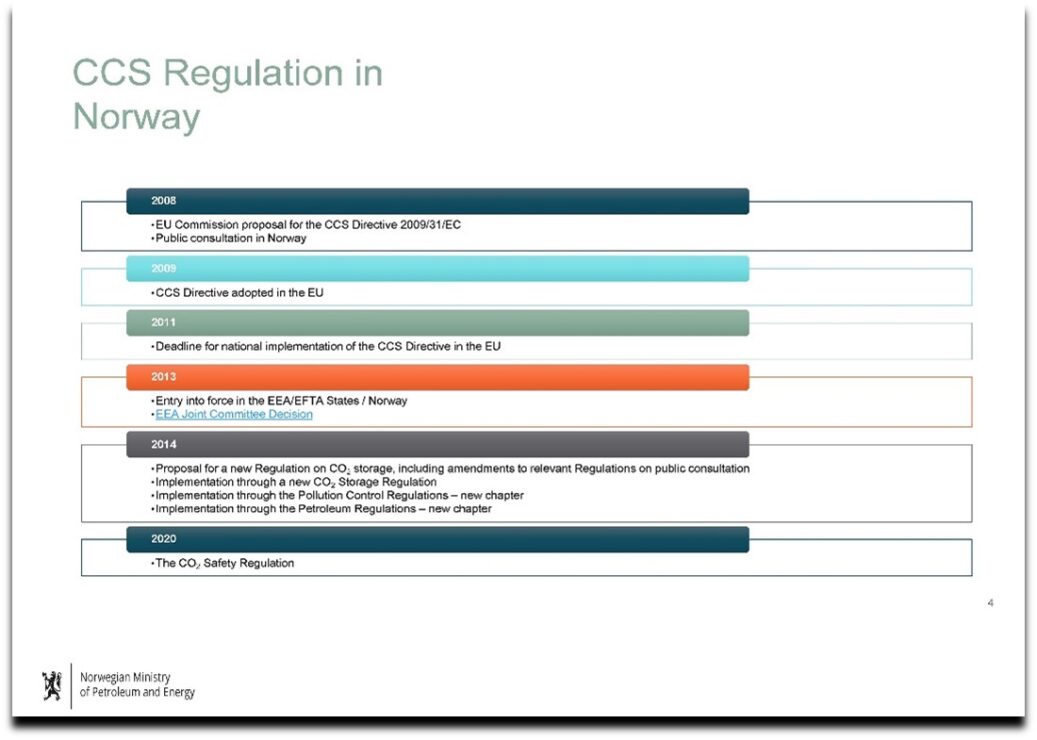

After the implementation of the CCS Directive into Norwegian law in 2013, the country has registered continuous developments in the CCS regulatory framework and adopted a Norwegian CCS strategy in 2014. Based on the strategy and the ambition of the Norwegian government to realise a cost-effective solution for full-scale CCS demonstration in Norway, the CCS project Longship was launched in 2020[4].

Figure 2: CCS Regulation in Norway[5]

As CO2 storage development in Norway has significance for the whole of Europe, Norway was keen to adopt the London Protocol and the amendment to Article 6, which allows the export of CO2 for CCS purposes. Norway approved the amendment in 2010 and since been encouraging more countries to do the same. However, as in 2019 only a few parties to the London Protocol accepted the amendment, the country joined forces with the Netherlands to put forward a proposition allowing for the provisional application of the 2009 amendment while waiting for its formal entry into force[6].

The work of the government is now focusing on establishing bilateral agreements to enable the cross-border transport of CO2 for permanent geological storage on the Norwegian continental shelf, in order to be compliant with the London Protocol.

CCS projects contributing to Norway’s climate ambition

The first two CCS projects in Norway, Sleipner and Snøhvit, played a significant role in the initial deployment of CCS in the country. According to Per Sandberg, Senior Advisor - Business Development at Equinor, these projects have been crucial in demonstrating that the technology could work.

However, it is the Longship project that introduced a new approach to structuring a full-scale CCS value chain in a cost-effective way. Longship is an unprecedented CCS project in construction since 2021, which aims to catalyse CCS market development in Europe in order to reach long term climate goals in Norway and the EU.

Figure 3: The Longship Project[7]

Aslak Viumdal, Senior Advisor at Gassnova, provided an overview of this innovative project, which is a public-private cooperation. Longship’s objective is to capture both biogenic and fossil-based CO2 from hard-to-abate industries and establish flexible and open-source transport and storage infrastructure.

The project developed by Gassnova together with the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and industrial companies involves two capture players, Heidelberg Materials (a cement plant in Brevik) and Hafslund Oslo Celsio (a waste-to-energy plant in Oslo), as well as a transport and storage solution offered by the Northern Lights consortium.

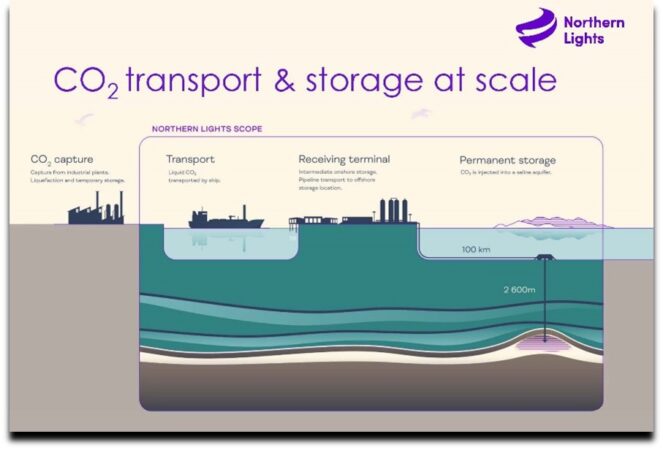

Børre Jacobsen, Managing Director of Northern Lights, provided further insights on the status of their transport and storage solution, which is more than 70% complete and on schedule to commence operations in 2024.

Figure 4: The Northern Lights Project[8]

Following the delivery of the Longship Element in 2024 (Phase 1), Northern Lights is planning to increase the injection capacity of its facilities from 1.5 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) to up to around 5 Mtpa of CO2 (Phase 2). However, in order to be a commercial investment, Northern Lights needs customers able to capture and deliver the CO2.

Once Phase 2 is completed, the ultimate goal is to go beyond 5.2 Mtpa of injection capacity and develop a commercial opportunity to meet market demand and drive further expansion.

According to Mr Sandberg, Northern Lights has changed both the regulatory and industrial thinking around CCS, as it represented a market opener for the technology and made CCS available and accessible to European users. The project also showed that there was a real interest in CCS across several industrial sectors.

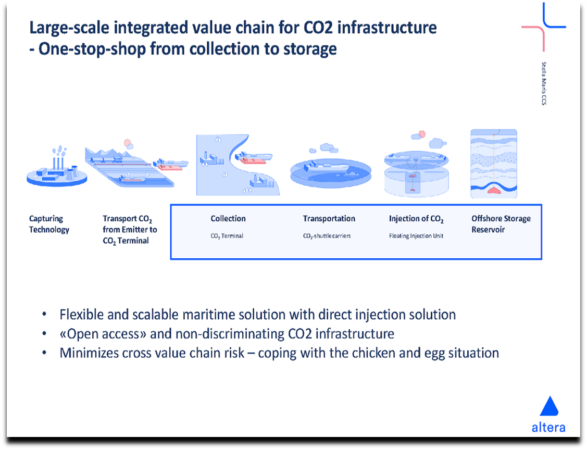

Finally, another example of a large-scale integrated infrastructure value chain is offered by the Stella Maris CCS project.

Johanne Koll-Hansen Bø, Vice-President and Head of CCS at Altera Infrastructure, delved into the project and its long-term vision to build an open access and non-discriminating CO2 infrastructure for multiple emitters across Europe.

Stella Maris CCS aims to minimise the cross-value chain risk through a one-stop-shop integrated infrastructure value chain solution from collection to storage, and offers a flexible and scalable maritime solution for captured CO2 from industrial sources, able to store 10 Mtpa of CO2.

Figure 5: Stella Maris CCS[9]

Lessons learned from the development of the projects

CCS investment incentives and a fit-for-purpose regulatory framework

During the webinar’s presentations and panel discussion, the speakers noted the difficulty of making the business case for the CCS industry, and that most of the regulation for CO2 storage is based on the experience of the oil and gas sector.

For CCS to be a profitable and cost-competitive solution, it is crucial to build the business case in partnership with project developers, customers and authorities. Regulatory bodies need to establish fit-for-purpose regulations for the CCS industry more in line with the CO2 storage business model.

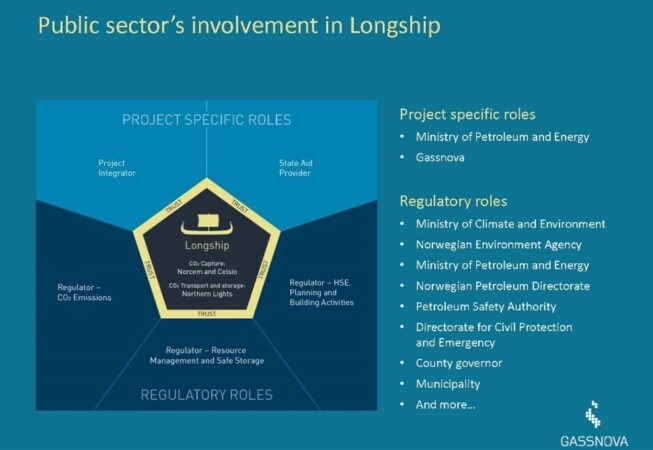

In particular, Mr Viumdal affirmed that when Longship was developed, the regulatory framework in place was not providing sufficient incentives for CCS investments. Due to the innovative nature of the project, some challenges also emerged as regulations were not aligned with the design of Longship’s whole value chain. However, several public sector bodies have been involved in regulating various aspects of the CCS value chain, and regulations have been developing in a positive direction in recent years.

Figure 6: Public Sector’s Involvement in Longship[10]

Ms Koll-Hansen Bø pointed out that large-scale full-value chain projects are highly capital intensive, but with the right commercial model it is possible to make these projects investable and scale up the CCS industry. She also stressed the importance of always taking costs into consideration when commercialising these projects and ensuring industry diversity within the value chain.

To implement a full-scale CCS chain as complex as Longship, both national subsidies and public and private forms of collaboration are crucial[11].

In particular, as the Longship project involves various industrial sectors, the Norwegian government decided the best way forward was to establish separate tailor-made state aid agreements with each company involved in the value chain[12]. As taking the risk for the whole CCS value chain was seen by the industry as an investment barrier, the state assumed a coordinating role, while Gassnova focused on integrating the full CCS chain and following up the staid aid agreement with the individual actors.

CO2 capture objectives vs available CO2 storage capacity in Europe

While the number of CCS projects in Europe is increasing, there is currently no developed commercial market for CO2 storage across the region, which results in a mismatch between CO2 capture potential and available storage capacity.

Ms Koll-Hansen Bø noted the storage projects underway in Europe have the capacity to receive around 30-40% of the CO2 expected to be captured by the facilities currently in the pipeline.

This represents a critical obstacle to the development of CCS in the region. By some estimates, around 350 Mtpa of CO2 might need to be captured in Europe by 2050[13], which makes it essential to take steps towards the development of new offshore reservoirs. Despite the interest in CO2 storage in Norway, the urgency of developing these reservoirs remains, as it might take several years to have them ready for injection.

Growing acceptance and interest in the technology

Panel members noted that recognition and acceptance of CCS as a crucial climate mitigation solution is growing and the market in Europe is showing increasing interest in CCS. The examples set by Longship and other CCS projects, the increasing number of companies committed to reaching net-zero targets, and policy developments in Europe are contributing to this.

Conclusion: A rapid ramp-up is needed

What emerged from the panel discussion among these CCS front-runners in Norway is that if CCS is to play a crucial role in the net-zero transition, a large, open, competitive and diversified market setting the conditions to stimulate industry and scale up deployment of the technology as fast as possible is needed.

CCS should not be seen as a transitional technology, but as a climate solution with a crucial role to play in the transition to a carbon-neutral economy. To make the technology a cost-competitive climate solution, a holistic regulatory approach that provides predictability and makes CCS investable is required. A fit-for-purpose regulatory framework needs to be developed to be efficiently applied to CCS hubs and clusters, as well as to multimodal and cross-border transport patterns, and be suitable for all players interested in entering the CCS industry.

To ramp up CCS deployment, predictability is needed around the transport and storage of CO2, as well as the right incentive schemes to help emitters advance their final investment decisions.

As financing CCS projects require significant investment, more funds at the EU and national level need to be granted to help projects get off the ground. Making the funding application process simpler and quicker is also crucial to accelerate the scale up of CCS.

Financial security requirements for CCS should include a risk sharing mechanism for long-term liability. An industry-wide insurance scheme that could be leveraged by the whole CCS industry, as well as a common fund at a national or regional level to facilitate financial security of the long-term CO2 liability, might be a solution.

The permitting process also needs to be accelerated in order to build CCS projects more rapidly, with more human and technical capacity required. Monitoring processes are crucial to confirm that CO2 is stored permanently and safely, but must allow for faster deployment.

The short-term priority is to start transporting and storing CO2 as soon as possible and establish bilateral agreements that can facilitate the transboundary movement of CO2. These agreements provide clarity to both business players and governments on the state responsibility, reporting mechanisms and long-term liability. As part of this process, it is important to consider not only the London Protocol, but also the OSPAR Convention, the Paris Agreement and relevant EU legislation.

[1] Global CCS Institute, Jacobsen, B., Koll Hansen Bø, J., Sandberg, P., Svenningsen, S., Viumdal, A. (2023, March 13). CCS Commercial and Regulatory Frameworks: Lessons Learned from CCS Front runners in Norway [PowerPoint Slides]. Available at https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/GCCSI-Webinar-CCS-Learnings-in-Norway-final.pdf

[2] Brundtland, G.H. (1987) Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Document A/42/427. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811?ln=en

[3] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2004). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: The First Ten Years. Climate Change Secretariat. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/publications/first_ten_years_en.pdf

[4] Gassnova, S. F. (2022). Regulatory Lessons Learned from Longship. Available at: https://ccsnorway.com/publication/regulatory-lessons-learned/

[5] Global CCS Institute, Jacobsen, B., Koll Hansen Bø, J., Sandberg, P., Svenningsen, S., Viumdal, A. (2023, March 13). CCS Commercial and Regulatory Frameworks: Lessons Learned from CCS Front runners in Norway [PowerPoint Slides].

[6] Meld. St. 33 (2019–2020) Report to the Storing (white paper) Longship – Carbon capture and storage. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/943cb244091d4b2fb3782f395d69b05b/en-gb/pdfs/stm201920200033000engpdfs.pdf

[7] Global CCS Institute, Jacobsen, B., Koll Hansen Bø, J., Sandberg, P., Svenningsen, S., Viumdal, A. (2023, March 13). CCS Commercial and Regulatory Frameworks: Lessons Learned from CCS Front runners in Norway [PowerPoint Slides].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] CCS Norway, Public and Private Cooperation.. Available at: https://ccsnorway.com/public-and-private-cooperation/ (Accessed on 24 October)

[12] Ibid.

[13] IEA (2020). CCUS in Europe in the Sustainable Development Scenario, 2030-2070. Licence: CC BY 4.0. Available at: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/ccus-in-europe-in-the-sustainable-development-scenario-2030-2070

This piece was written by Daniela Peta, Communications and Advocacy Associate with the Global CCS Institute.